I think I’m afraid of commitment. When I was a child, it was a small matter to sit in front of the Nintendo 64 for hours. Time meant nothing to me; now, it’s all I think about. I look at upcoming games, at the hundreds of hours of playtime required, and I cannot fathom where to find time to actually play videogames.

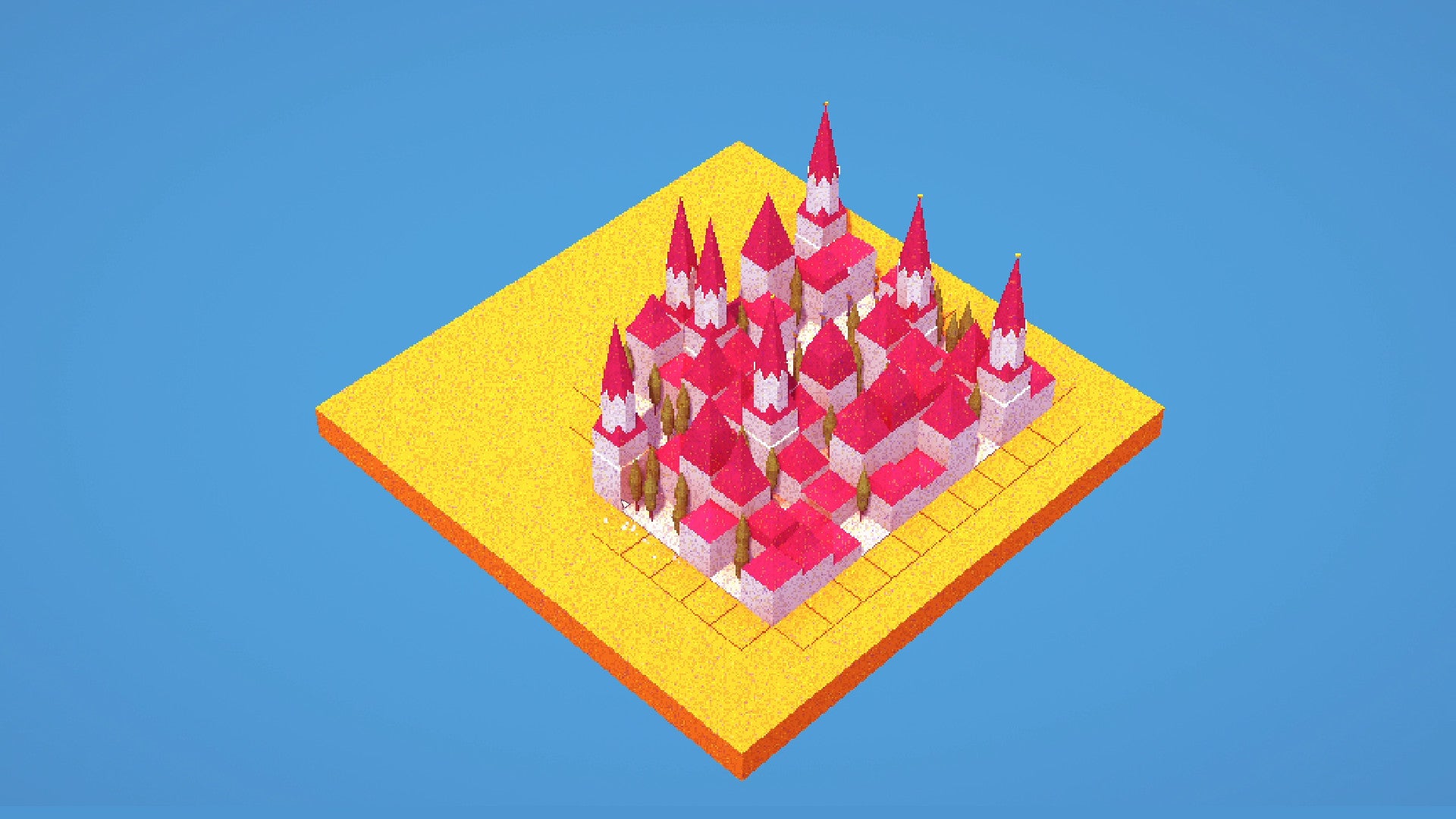

It’s ironic, then, that my solution to the resulting crippling inertia is to sink over a hundred hours in Islanders. This is a game that makes no demands on my time, in which the only aim is to slide buildings, Tetris-like, against each other to create dense and tranquil cities.

It’s part of a growing trend in casual games. While blockbuster titles become bigger, brighter, and more bombastic, these games – appropriately – gently slide into the mainstream to offer a less demanding alternative. It was an ascendency cemented when Unpacking beat games like Deathloop and Metroid Dread to be named BAFTA game of the year back in April.

To find out more about the genre – and, perhaps, discover why I love it so much – I spoke to Paul Schnepf. One third of Islanders developer, Grizzly Games.

Grizzly Games first rose to prominence with 2017’s Superflight, a casual gliding sim in which the inception of the aesthetic style found in all of Schnepf’s games can be seen. But the beginning of this new trend reaches back further. Schnepf recalls playing Settlers 2 and Age of Empires when he was younger and we chat about how we both found the warfare of Age of Empires overwhelming, preferring to hide in a corner of the map and build cities.

Schnepf and his Grizzly Games colleagues, Jonas Tyroller and Friedmann Allmenröder, “found most of them [city-building games] complex,” Schnepf says. “It always stressed me out that you have to be in so many different places at the same time with your mind.”

While we were forced to create a game within a game when we were younger, the Grizzly Games team set out to transplant that experience into its own, dedicated system. The result was Islanders.

“We wanted to create something that lets you actually focus on just building things,” Schnepf says.

It’s interesting that paring back established mechanics to something less overwhelming drives so many placement-style games. Compared to old city-building sims and their successors, like Two Point Studio’s recent Two Point Campus, Islanders asks only small inputs from the player: look at a list of buildings, arrange them, and place them. It’s almost like gardening.

This focus on a single, robust mechanic appears to drive Schnepf’s games so far. Where it’s undistracted flight, tending to an industrial garden, or the rhythm of The Ramp, another game of small arenas, in which you guide your skateboarding avatar around bowls and ramps via a series of rhythmic inputs.

“I was always a bit sad that all the skateboarding games out there focussed on street skating,” Schnepf tells me. “I really wanted to focus on and try to capture this kind of experience for both people who love vert skateboarding and people who didn’t have the experience so far, and I think this element of rhythm is most important there.”

At first glance, The Ramp feels removed from the ostensible theory set down in Islanders and now The Block – in which, instead of an island, the player is tasked with creating cute structures on tiny patches of land. So why mention a skateboarding rhythm game amid placement-style experiences? Well, there’s rhythm to every videogame. It’s just casual games enjoy a much gentler rhythm. The rapid tapping of The Ramp may make its rhythm obvious, but the considered tempo of Unpacking, Cloud Gardens, and Islanders is just as meaningful.

That more considered approach is important to Schnepf; the ability for the player to reclaim control of their own time. “That probably came from myself having less and less time for playing videogames,” he says.

That lack of temporal obligation feels core to the appeal of games like Islanders and Cloud Gardens. With the stress of reaching a section in Final Fantasy 15 that wouldn’t let me save for well over an hour or of losing progress to Stray’s arbitrary checkpoint system fresh in my mind, I know Islanders won’t do that to me. I can stop when I want.

Why exactly this style of game has proven so popular in the last two years is hard to pin down. It’s easy to look at the lockdowns of 2020 as a primary catalyst. Almost overnight, swathes of us gained unprecedented free time. But I wonder if it goes further, if the early days of the pandemic just showed us the value of relaxing. When chaos became overtly external, games that, as Schnepf puts it, “wouldn’t demand a fixed amount of time” suddenly became a much-needed balm for agitated and distracted minds.

Moreover, the limited space of placement-style games – whether it’s an island, a house, or a patch of earth floating in a vacuum – gave us small, controllable areas on which to focus in the face of catastrophic shared experience. “We wanted the player to be able to see all of their city – or at least most of their city – all the time,” Schnepf says of Islanders. “So, you don’t have to keep all those different places in your mind and think about them constantly; so you can just always see what’s there and that’s enough.”

As I grew steadily more concerned about what was going on outside, being able to hyperfocus on something undemanding for an ambiguous period of time helped ease my growing anxiety.

It’s why I’m excited about The Block. Released today on Steam, it’s a prospective balm for the continuing chaos around us: small, accessible episodes compared to releases that demand you give away much of your future free time.

Curiously, when I ask Schnepf what he plays, casual games are low on the list. He tells me his most played games on Steam are Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 2 and Counter Strike. It feels like a sharp contrast: the hectic FPS multiplayer and the tranquility of The Block and Islanders.

Yet, it’s one I understand. Strip away the complexities and they’re fundamentally similar. Small, manageable chunks of time that can be extended in defined increments: whether it’s moving to a new island in Islanders or starting a new match in Modern Warfare 2.

“Yeah,” Schnepf says when I suggest this. “I think that’s actually something that always mattered to me, that I didn’t have to make this massive commitment.”

There is a human phenomenon in which we feel compelled to dig holes. Head down to the beach and chances are you’ll spot someone merrily excavating. A few times in the last couple of years, I’ve found myself looking into the garden and thinking, “Yeah, probably feels good to dig a hole.”

When asked by Slate why she digs, Leanne Wijnsma said, “You kind of stop thinking… You only have one goal, and that is extremely relaxing.”

Not all of us can dig a hole. But I wonder if playing a game like Islanders isn’t so different – like digging for the mind. A singular, focussed, low-impact exercise for cognitive muscles. Perhaps I’m thinking too much into it. But as I grow more accustomed to how frantic and unhealthy the pace of the modern world is, I wonder if the occasional foray into watching little blocks rest neatly against each other wouldn’t be a good thing for all of us.

www.eurogamer.net